IlliniSat-0 was always designed to be inexpensive. That's the point, isn't it? Take the NewSpace mantra of using commercial parts and good engineering to build reliable stuff for less money, and turn it up to 11. Use the fact that capable computers can now be had for less than $10 in the form of microcontrollers. Use highly integrated and pre-tested devices for power management to reduce the risk of making a mistake, and speed up development. The IC designers at ST, TI, etc. have really been pushing the boundaries of integration in the past 10 years, and it's finally time for us, both as LASSI and as the space industry in general, to figure out how to take advantage of that. A good design problem! Perfect!

... And then all of a sudden, all of that new technology disappeared.

Many people have heard about the semiconductor shortage (hereafter referred to as the "part shortage") because their new phone models were delayed, or they couldn't upgrade their computer. Others may be familiar with it because car production has slowed to a crawl, so new cars are hard to come by.

Our modern lifestyle relies on the easy availability of ICs to put in our devices, so when the supply of magic rocks stopped earlier this year, it reverberated throughout the economy. Those inexpensive, reliable computing devices I talked about earlier, microcontrollers, changed the design of just about every electrical device. Being able to write software for a microcontroller rather than doing complex electronics design, or electromechanical system design, was a massive improvement for the capabilities of our devices. (Ever wondered why dishwashers and laundry machines are all moving towards "computer control"? Even the low-end ones? It's because doing it with a microcontroller has become cheaper than the mechanical timers they used to use.) It was an improvement that was so clear that everyone started doing it, and it (silently, somehow) revolutionized the industry. So when these magic, revolutionary devices suddenly disappeared, so did everything else.

Even if you haven't seen the effects of the chip shortage in person, hopefully it is clear that its impacts, are, right now, huge for the entire supply chain of just about every product. Right now, It's difficult to get products that we otherwise would be able to get, because there aren't enough parts to make them. Easy. That's true right now.

But what about next year, or the year after? The chip industry will recover, and we'll be able to get parts again. Cars won't be super expensive, I'll be able to upgrade my GPU, and my new dishwasher will have buttons and LEDs again. Great, right? Let's take a step back in the product lifecycle real quick. This blog's not about consumer technology that's already on the shelf yet. I'm designing tomorrow's technology, much like every engineer in industry, not today's technology. How has it impacted me?

The team and I have been slowly (COVID pace) working on designing the electronics and supporting hardware for the IlliniSat-0 bus over the past couple of years. For being a relatively simple system, it is quite complicated to engineer since we're using good engineering to overcome our mediocre (in terms of reliability) parts, so until very recently illiniSa-0 has existed almost entirely on paper. With the immediate impacts of COVID lessening, like the availability of the vaccine making in-person meetings and lab work possible again, it is finally time to pick up the pace and get some of these designs tested, iterated, and finalized. We can't really say we have a satellite that meets the requirements and is up to our standards until we've tested it and verified that it is. So, logically, we should be taking our paper designs and making them as soon as humanly possible.

... Except we can't, because we can't get any parts.

Many of our satellite boards use microcontrollers that are widely used in industry. This was very intentional- microcontrollers that are widely used are widely available and typically have long design lifetimes (i.e. they will not be discontinued by the manufacturer for a long time) so they are perfect for a bus that is designed to be cheap and have long longevity. The only flaw with this logic is that if something unthinkable happens, say a chip shortage caused by a global pandemic, there will be a ton of demand for the chip you have chosen because the industry that widely used it, now widely needs it. Your order of 10 microcontrollers for your small run of spacecraft is now stuck in line behind the tens of thousands that are needed by companies making consumer products. You can't get any chips for prototyping, much less manufacturing. The cutting edge has to wait for the blunt edge to move out of the way.

I foresee this becoming an industry-wide problem. This inability to get parts to make development boards with, to prototype with, and to test with, is liable to stunt the growth of technology in ways that we will start to see very soon. Not having parts to play around with means that design engineers can't take advantage of better technology to make their designs better. Not having parts for prototypes means there's no way to demonstrate technology to determine feasibility, to get funding, or to get the public interested. Parts being missing for testing means that (assuming testing isn't skipped entirely) advanced designs will need to sit on the drawing board for a while before they can be verified and produced. All of these things will incur delays and likely put the brakes on our otherwise rapid rate of technology development. Will it halt development completely right now, leading to total stagnation a year from now? I don't think so. There are a few factors that will help mitigate the effects of the shortage, some of which are helping us for IlliniSat-0 development.

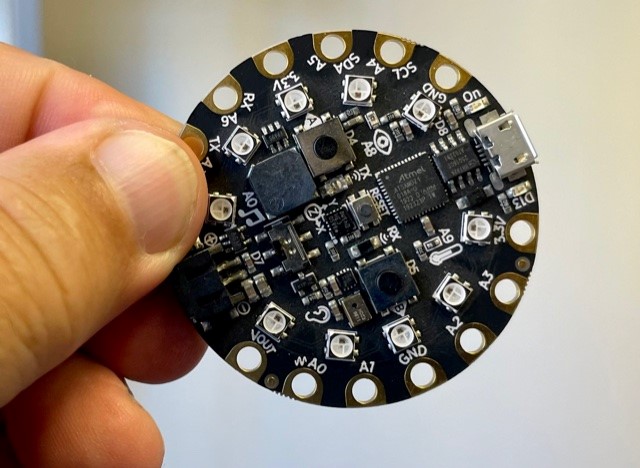

One major factor that is really saving our bacon on IlliniSat-0 development is a simple one: our high-performance boards in the bus use brand-new microcontrollers from ST that are too new to be used in commercial products yet. This means that, all other things being equal, they are not consumed in such volumes as commercial production of a product requires, so they are easier to get. This has proven to be true: I have been able to buy enough "smart" parts to be able to build the processing unit (ZPU) daughtercard, which is excellent news since it allows us to begin software development soon. Semiconductor companies have also been attempting to hold back enough chips to meet demand for their evaluation/development boards (TI LaunchPads, ST Nucleo/DISCO boards, etc.), another factor that will help mitigate a technological rut.

I am hopeful that these mitigation strategies, among others which are doubtlessly being implemented by engineering companies globally, will mean that the chip shortage becomes more of a speedbump for technological development, rather than a brick wall. Given the problems we are having with IlliniSat-0, I doubt there will be no impact at all. We're probably going to start to feel it in not too long, and the effects are likely to reverberate for years to come. I am optimistic that once the speedbump is passed, though, we will be able to put the pedal to the metal and speed on into the distance even faster than before.